|

|||||

|

I

was there! I was there when Yves Rossi arrived by jet-propelled wing

at the South Foreland lighthouse on top of Albion’s cliffs between

Dover and St. Margaret’s Bay. I knew he was coming that day but I

arrived quite by accident at the right time after a visit to Dover.

|

|

||||

|

Dover is an odd place, this coast is truly liminal as well as

littoral, it is a place that aliens head for and from where natives

hurry away. Today's two-way traffic sees, it seems, every dispossessed wretch from overseas

aiming for Dover in the back of a truck while wealthy patriots head

for holiday homes in the Dordogne or Tuscany driving smart 4x4s.

In

history, Julius Caesar landed on this coast in 55BC and fought on

the beaches between Dover and Deal with the woad tattooed,

promiscuous, drinking and brawling

Brittunculi (no change

there then). Claudius came later in AD43. The Romans eventually made

Dover their port of entry, building and maintaining a

pharos

on the cliffs either side of the port for their ships to aim for.

The Germans had Dover in their sights for

Operation Sea Lion during

WWII.

|

|||||

|

In 1909, Louis Blériot was another heading this way... |

|||||

|

Yves Rossi had had to wait for the weather like Blériot a century before him, Rossi leapt from a plane at 2500-m and his journey took 9 minutes; Blériot took off from a Calais beach and took 37 minutes. Rossi had an epoxy carbon fibre cloth wing, Blériot used double skin Continental fabric [Unbleached linen and nitrocellulose dope, one imagines] Rossi used Jet-A1 in four jet-turbines, Blériot used kerosene in three cylinders, Rossi had a chase helicopter, Blériot a fast boat. Both followed the same flight path and crossed the same 35-km stretch of water a ten decades apart. In this centenary year, I look back on Louis Blériot and his achievement in an article I wrote some time ago using text taken from the notice board above for details. |

|||||

|

It’s damp, very damp... it’s now October. The rain seems to be never

ending. As I park, the rain turns to a steady spray, a mist gassing

from a leaden, saturated sky. I make my way down a muddy path lush

and slippery with fluorescent green mosses. I brush past dank

thicket festooned with water droplets hanging like diamond

cabochons; they soak me more than the drizzle ever could. |

|||||

|

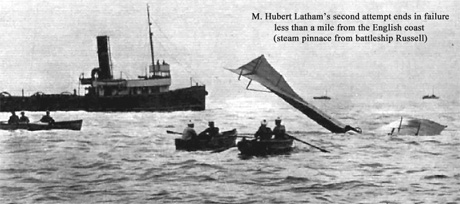

The year was 1909, the tail end of La Belle Époque in France and of the Edwardian Era in England; it was 25th July when Louis Blériot became the first man to fly across the English Channel. Blériot was, in fact, the first man to make an overseas flight. He gained worldwide recognition; new technologies came thick and fast in those days and they were publicly celebrated widely. The Channel Crossing was the culmination of 9 years of experimentation for the French auto engineer and inventor and the final lap of a gentlemanly race that was going on at the time. M. Hubert Latham, a rival Frenchman had failed, just 6 days earlier, to make the crossing in HIS monoplane, the Antoinette. But for Latham's accident his name might have been the name to go down in the history books. |

|

||||

|

THE FLIGHT

The drama began at around 4.30am, dawning had occurred some 40 minutes earlier,

we are told. Dressed in his French-blue engineer’s overalls, covering tweed

clothes lined with wool for warmth, Louis looked around him determined to

accomplish a historic flight. With his close fitting cap pulled tight about his

head and ears, he spoke to friend M. Le Blanc who was scanning the horizon

endeavouring to catch sight of Albion under Aurora’s light. Le Blanc said the

wind was light and from the southwest. “Tout est prêt!”, he said. At 4.41am French time, when Blériot took off into the mist, a throng of spectators had gathered on a Sunday morning to witness the making of history. Louis is said to have wryly asked an English reporter covering the event, "Weech way eez Do-verr?", for there were no aerial navigation devices in those days. The aircraft climbed away from the sand dunes of Les Baraques, a small village near Calais, shaking under the strain of its 1200 revolutions as it cleared the telegraph wires along the cliff. His takeoff was the prelude to a perilous flight. Blériot had injured himself days earlier in a fuel explosion and his rival, Latham, too had recently had a ditching accident; one imagines Louis felt ready, if a bit serious minded, after the watery events that overtook his rival Hubert Latham. Blériot's only piece of safety equipment was an inflatable rubber tube in the middle of the fuselage, just less than 2-metres long, that he hoped might provide some buoyancy should he have to ditch in the channel. Fortunately, a fast rescue boat, the Escopette, was at hand in the event of an accident. |

|||||

|

THE DRAMA Shortly after his little plane took off and disappeared into the low cloud at 100-metres, Blériot lost sight of his motor torpedo ‘chase boat’ below. It was chosen for its 21-knot speed though it was not fast enough to keep up with the 38-knot monoplane! If this was worrying then the imminent failure of his unreliable Anzani 25 cheveaux engine as it began to overheat and lose power must have started to panic him. Providentially, a pantheon of capricious weather gods was watching Louis keenly that morning as they threw a small squall at him: the sudden downpour cooled his three tiny engine cylinders and he was able to push on. |

|

||||

|

The squall, of course, interrupted the south-westerly zephyrs of the early morning with 20-knot gusts that buffeted his fragile plane and threw if off course. Unbeknown to him, he was heading towards St. Margaret’s Bay, too far north. Nevertheless, Blériot spluttered on blindly, blithely unaware exactly where, or even if, he would make landfall; he must have been relieved to see the English Coast, the White Cliffs and the Castle. He turned south and made for Shakespeare Cliff on the other, southern side, of Dover harbour. |

|||||

|

|

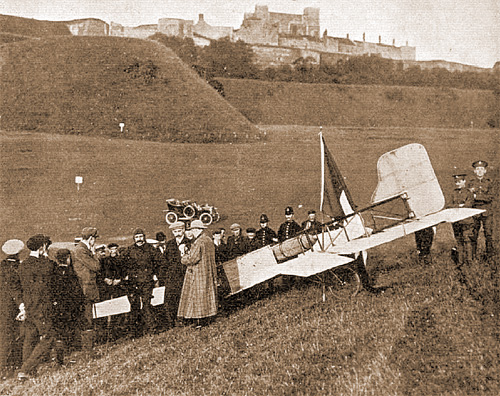

THE ARRIVAL

As he approached the coast, Blériot

searched for the gap in the cliffs and saw a man, a friend, M.

Charles Fontaine, waving a ‘French Tricoleur’. Fontaine had been

charged with finding a landing site. At 5.12am the intrepid

Frenchman ‘landed’ on English soil after a 37 minute flight from

Calais at 5:14 local time, his average speed was just 39-knots. |

||||

|

This historic feat of aviation, however, did not overwhelm H.M. Customs who

promptly arrived to register Blériot’s arrival in England. Being the first

foreign aeroplane to cross British borders there were no official forms for the

aircraft and, presumably, largely being of 'string and canvas', it was finally

registered as a yacht! |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

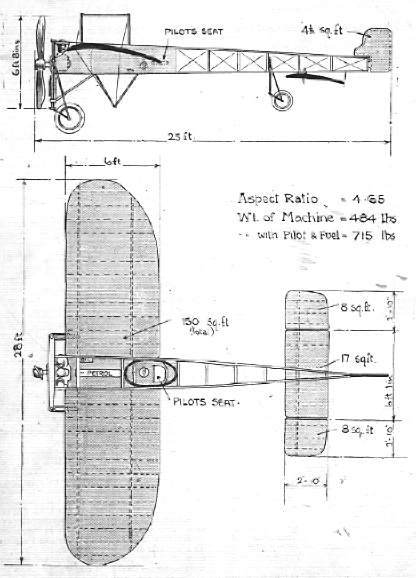

THE AEROPLANE

Blériot was an avid inventor and aeroplane builder, one of his inventions being

the Calcium Carbide/acetylene car lamp. The 25-hp monoplane in which he made the

flight had a three cylinder air-cooled Anzani engine; it was his eleventh

aircraft - hence its novel name - the Blériot XI! He had experimented with

towing gliders by motor boat on the River Seine and then, as lightweight engines

became available, he developed aircraft of various types ranging from box-kite

look-alikes, to a canard monoplane to a strange floatplane with elliptical

wings. The impetus for the flurry of French coast activity was the prospect of

winning the £1000 reward for the first successful channel crossing offered by

the Daily Mail which he won. |

|||||

|

AND FINALLY…

There were political consequences of the flight

— Lloyd George, The possibilities of this new system of locomotion are infinite, I feel as a Britisher, rather ashamed that we are so completely out of it.” |

|||||

|

Airframe improvements and larger, more reliable engines led to several single

and two seat versions of the aircraft. Blériot was later associated with the

makers of the famous Spad fighter. After the war, he formed his own company for

the development of commercial aircraft. He died in Paris in 1936. Blériot went

on to build somewhere around 10,000 aircraft for the French government and the

Allies during World War I. By the next year, the Blériot XI was in use by the

French and Italian military. Britain began flying it in 1912. When WWI began,

there were eight squadrons of Blériot XI variants in the French Air Service,

seven in the Royal Flying Corps and six in the Italian Air Service. |

|

||||

THE RIVALRY

THE RIVALRY