Background AD43-61

AD 41-54

Claudius

Aulus Plautius

Aulus Plautius left much of lowland

Britain mostly 'conquered' and under imperial control when he went to receive his

honours, an ovation, in Rome. He was replaced by a new governor brought in in

AD47, Publius Ostorius Scapula - a tough military man. It seems likely that the initial

cause of the rebelliousness and later revolt of the Iceni may have been due to

this man in

some part: the disarming of the Iceni and other tribes - this was a political misjudgement.

However, after Claudius'

invasion, when the whole of the army had marched on Colchester, the

real conquest began. Rome had its client states in East Anglia

(Prasutagus of the Iceni,) and in Hampshire/Sussex (Verica &

Cogidubnus controlling Atrebates/Regni/Belgae) and so felt secure on

these fronts and able to push away from Camulodunum by

sending the Legions out to the furthermost limits of control.

Legio XX remained in Colchester, Legio IX pushed

north and established a base in Lincoln (in the centre of the Iceni

it must be said), Legio XIV went northwest into the Midlands

and Legio II went west under Vespasian (well documented for

his 30 battles and 20 conquered hill forts) and after hard fighting,

subduing the Durotriges and Dumnonii, eventually established his

legionary headquarters in Exeter. [Richborough port was established

at this time as a supply base.] The next task was to conquer Wales...

Ostorius Scapula

The Iceni had willingly acceded

to Roman rule but Ostorius, Plautius' replacement in AD48, found all

was not well on the frontier; Caratacus, Cunobelin's anti-Roman son

had fled to the west. Intent on stamping out resistance as he

conquered further north and west, past the unofficial boundary of

the province left by Plautius as defined by the rivers Trent and

Severn, Ostorius disarmed the Iceni and Trinovantes. He didn't want

a mass of armed, perhaps untrustworthy, tribes of behind him. They

rebelled but were put down by Ostorius.

As the Romans advanced so they

built roads for supplies and reinforcements, it was a slow business. Under Ostorius' rule the pugnacious Caratacus had

been rebel-rousing and causing lots of trouble for the Legions first

in Wales, where he lost his wife and children, and then the

northwest. Eventually seeking sanctuary in Brigantes' land he was handed over by

a (threatened) pro-Roman

Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes; Ostorius Scapula returned with his

prize to Rome; he had done a lot for the empire and died, worn out

by guerrilla struggle, in AD52. Ostorius' control was good and he

accomplished many things during his tenure including the creation of

Camulodunum as a Colonia with veterans and Verulamium as a

Municipum of Latin citizens, London was just a Vicus at

that time.

AD 54-68 Nero

Aulus Gallus

Aulus Didius Gallus, his

replacement, was an

impressive soldier and former consul with many campaigns behind him but he had

troubles to face in Britannia too - with the confederation of the

Brigantes and Venutius (husband of Cartimandua). The conquest

advance stalled and Gallus' consolidated his position strengthening

the forts and quelling Wales and building a fort a Wroxeter where

Legio XIV arrived. Around AD54 Claudius died under

suspicious circumstances and Nero became Emperor. Nero had little

interest in Britain but nevertheless appointed a new governors to

Britannia, Q.

Veranius in AD57 then C.

Seutonius Paullinus in AD58 determined to conquer Wales.

Seutonius Paullinus

There had been fighting on the

Welsh border for a decade or more against the tribes of the

Ordovices and Silures in AD58; he subdued them finally turning his

attention to Anglesey and the Decangli in AD59. Anglesey was

breadbasket to some tribes, rich in copper and a haven for all

Druids and Romans didn't like them or their rituals. Seutonius

forces crossed the Menai Strait and fought the Druids et al .

The Romans wiped out all of them including the "funereal clad women

with blazing torches" and a fort

was built. Just at this time news arrived of the Boudiccan revolt.

Read

Tacitus' account

of Boudiccan revolt

Read Cassius Dio's

on Boudiccan revolt

Boudicca

As mentioned above, the disarming

of the tribes was one cause of simmering discontent compounded by many other things.

While the Legions had been away securing the north and west

Camulodunum had been founded as a Colonia and settled with

veterans from Legio XX. These men had been given, or more

likely appropriated, the best Trinovante and Iceni farmland for

themselves and their families. Their treatment of the locals, whom

they had conquered, were treated worse than slaves and exploited,

humiliated, oppressed. These things, and more, eventually exploded in AD60 with the Boudiccan

revolt. It was

Presutagus' death that precipitated the revolt...

He had been king of the Iceni and

husband to Boudicca and bequeathed half of his estate to his wife

and half to Nero - it was a big mistake for he had not done it

correctly. He thought to preserve the

monarchy for his family but with his death, in Roman eyes, died his

'treaty' with Rome and, of course, Rome did not like kings! Officials came to seize his property but

Boudicca, his widow, resisted and was flogged; her daughters were raped - and so

it began - Britannia almost lost to Rome. Nero had been worried

about Britannia but on hearing the news of the rebellion he was

horrified, he was on the verge of deciding to pull out altogether.

Someone had made a big mistake.

The Legions were dispersed across the land - Legio II in

Exeter, Legio IX in Lincoln and XX and XIV with

Paulinus in Anglesey. Camulodunum was undefended, there was no fort

there, no garrison, no discipline, the veterans were deemed all that

was necessary. All the building effort had gone into civic buildings

especially the huge temple dedicated to the deified Claudius, a real

anathema to the Trinovantes who saw it as a 'citadel of tyranny' to

quote an documentary source. Boudicca seized her opportunity.

Colchester was taken by hordes of angry tribesmen, half-timbered

houses went up in flames, the temple was the last refuge for the

Roman citizens and veterans, they were wiped out. Legate

Petillius Cerealis , legate of Legio IX up in Lincoln

received news of the rebellion but as he rushed to aid Colchester

ran into an ambuscade and lost a vexillation of maybe 2000 men, he

retreated.

Paullinus, fighting in Anglesey,

wasted no time in starting the 250 mile/2 week journey back to

save the southeast. He had Legio XX and XIV and headed

for London. Legio II was called from Exeter but their

temporary leader, Poenius Postumus, refused to come to their aid.

Short of this legion Paullinus realised that he did not have enough

men to defend London when he arrived and abandoned the trading town

to its fate. Boudicca charged with success and blood-lust fell on

London and Verulamium. It was slaughter, it's said,

70,000 dead soldiers and allies were lost. Paullinus however, was a

shrewd leader and chose a site for a last stand which he chose. It

was somewhere near Coventry we assume. His men lined up against a

masse of Britons and was perhaps outnumbered 20:1. The Britons

assumed they would win and even brought their animals, wagons and

families to the battlefield to spectate. Roman discipline and

armament won the day - 80,000 plus dead Britons were killed.

In the subsequent weeks and

months reinforcements arrived from Germany and the whole of the

rebel areas were destroyed, razed to the ground. The coward Postumus

fell on his sword, Boudicca resorted to poison. The Roman grip on

the province tightened and they built more forts but now there were

serious consequences for the Britons. The Iceni and Trinovantes had

not sown crops in AD60 and 80,000+ breadwinners were lost to the

tribes.

A new Procurator, C. Julius

Classicianus was appointed to London after his predecessor Catus

fled to Gaul. Classicianus was to be a great man with a different

attitude to Britannia for he was a provincial from Germany. He had

no fear of Paullinus who was recalled to Rome on some pretext and

replaced by P. Turpilianus as new governor of Britannia in the

latter part of AD61.

See if you can trace the

Romans Roads in your area.

The

nearest stretch of Roman Road to me, living in Herne, is that which

runs from Sturry/Fordwich through Hoath to Hillborough and on to

Reculver. This road presumably carried traffic from the old Roman

fort of Regulbium (Reculver) to Canterbury (Durovernum).

Click East Kent map left, for Roman roads.

What were

the roads made of, when were they built and why?

Roman roads were built for moving men and

supplies around the empire. From the bridgehead at Richborough the

first

road was built to Canterbury, from Canterbury to Rochester, to

London, then St. Albans and then on to Colchester. In east Kent

additional roads were built from Canterbury to Reculver, to Lympne

and later to Dover.

Roman roads very often followed ancient

trackways and local boundaries but sometimes ignored things

like barrows. In the 1st century the Romans built 10,000 miles of

road. Engineers took 3 or 4 days to build one mile of road. Forts

were built at strategic points along the route as the area was

quelled consolidated.

The tribes of Kent were pro-Roman

so road building must have gone on at a pace without too much

hindrance. After

roads were constructed milestones were laid down. Distances were

measured in Roman miles. (milia passum m.p.) The roads helped

the Romans to calculate land areas and hence, taxes. A list of roads

was created by Antonine, Itinerarium Antonini Augusti, in

the 2nd or 3rd century.

Simply a road was constructed in

the following manner.

A ditch was dug on either

side of the proposed road.

Boulders were and the

spoil from the ditches was piled on the road.

This built up layer was

called the agger.

Next the edges of the

ditches would be lined with kerbstones.

Flat stones were now laid

for the road surface.

Lastly an infill of gravel

was used to level the surface.

There are alternate versions

depending on the available materials...

This

from:

http://www.dl.ket.org/latin3/mores/techno/roads/construction.htm#top

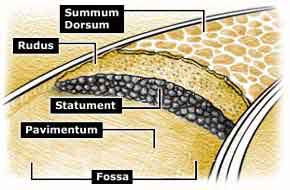

"The field engineer, assisted

by a stake man aligned the road with a groma and ran levels with

chorobates. A plough

was used to loosen the soil and mark the trench (fossa) margins.

Workmen dug trenches for a roadbed with a depth of 6 to 9 feet.

The

earth bed was tamped

firm. The foundation of lime mortar or sand was laid to form a

level base (pavimentum). Next came stones of about 4 to 5 in. in

diameter, cemented together with mortar or clay (statument).

This layer could be anywhere from 10 inches to 2 feet deep.

The

earth bed was tamped

firm. The foundation of lime mortar or sand was laid to form a

level base (pavimentum). Next came stones of about 4 to 5 in. in

diameter, cemented together with mortar or clay (statument).

This layer could be anywhere from 10 inches to 2 feet deep.

The next course (rudus) was 9

to 12 inches of concrete filled with shards of pottery or stone.

Atop this layer was the nucleus, a concrete made of gravel or

sand and lime, poured in layers with each layer compacted with a

roller. This layer was one foot at the sides and 18" at the

crown of the road. The camber was to allow good drainage.

The top course was the summum

dorsum, polygonal blocks of stone that were 6 inches or more

thick and carefully fitted atop the still moist concrete. When a

road bed became overly worn, this top course was removed, the

stones turned over and replaced. A road was 9 to 12 feet wide

which allowed 2 chariots to pass in each direction . Sometimes

the road was edged with a high stone walkway. Milestones

indicated the distance. A cart, fitted with a hodometer was used

to measure distances. Later maps detailed routes, miles towns,

inns, mountains and rivers. The first roads were quite straight

going over hills rather than around them."

* groma = device with 4

plumb lines for creating straight lines across the landscape

as seen in "What the Romans did for us - Adam Hart-Davis."

* hodometer device for measuring distances as described by

Vitruvius.

as seen in "What the Romans did for us - Adam Hart-Davis."

* chorobate = early form of spirit level

Or this: http://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-road-construction.php

"First the two parallel

trenches were built on either side of the planned road, with the

resulting earthworks, stone, etc., being dumped and built up in

the space between the two ditches. The Agger, as this was

called, could be up to 6 ft. (1.8 m) high and 50 ft. (15 m)

wide. Alternatively it could be very slight or almost

non-existent as was the case with most minor roads.

Next, the diggers would make

a shallow 8 to 10 foot wide depression down the length of the

agger, and line the edges with kerb stones to hold the entire

construction in place. The bottom of this depression would then

be lined with a series of stone fillers. 6 to 8 inch stones

would form the foundation layer, with fist sized stones placed

on top. In early roads the remaining gap would then be filled in

with course sand to fill between the stones and to cover them by

approximately 1 ft. Later roads may have used Roman volcanic

concrete to mix the entire mixture together making the whole

structure more solid. The road surface was then laid down using

large, tight fitting, flat stones that could be found and

transported locally. These larger surface stones would be cut to

fit when possible to make the surface as smooth and seamless as

possible.

Bridle paths were then dug

and smoothed, leaving the earth unpaved for horse travel. The

roads were built for infantry, and it was easier on horse hooves

to walk alongside the stone roads. Though the Romans did use

horseshoes, they were tied on to the hooves, not nailed, making

them unstable. Additionally, during the construction, forests

and obstacles on either side of the road could be cleared to a

considerable distance to guard against ambush attempts."